Sonoji 浅ノ字

My wife and I just finished a wonderful lunch of tenpura and soba at Sonoji, a Michelin one-star restaurant that is only a few second walk from our home in Ningyōchō. When Sonoji first opened I often went for soba lunch, with a piece or two or three of ala carte tenpura. But those days are long gone; it is now course only, although in the evening there are two choices for the course, one a bit bigger—and more expensive—than the other.

Suzuki san, the owner, is from Shizuoka where his father has, and I believe grandfather before that had, a well-known soba restaurant. So naturally, almost all the ingredients are from Shizuoka, including the soba and of course, the wasabi. There were only a couple of exceptions today necessitated by their seasonality, some things coming into season sooner due to where it is from.

My wife and I each ordered a bottle of beer, me a Baird Pale Ale, she a white beer, both from Shizuoka, of course. We were seated at the left end facing the chef of the eight-person counter, our seats being the best for soba as we are always the first to be served, meaning what we eat is served under the best conditions, the tenpura crispy and hot, the items removed from the oil when they are first ready, not after another minute or even thirty-seconds of cooking as with the people at the far end.

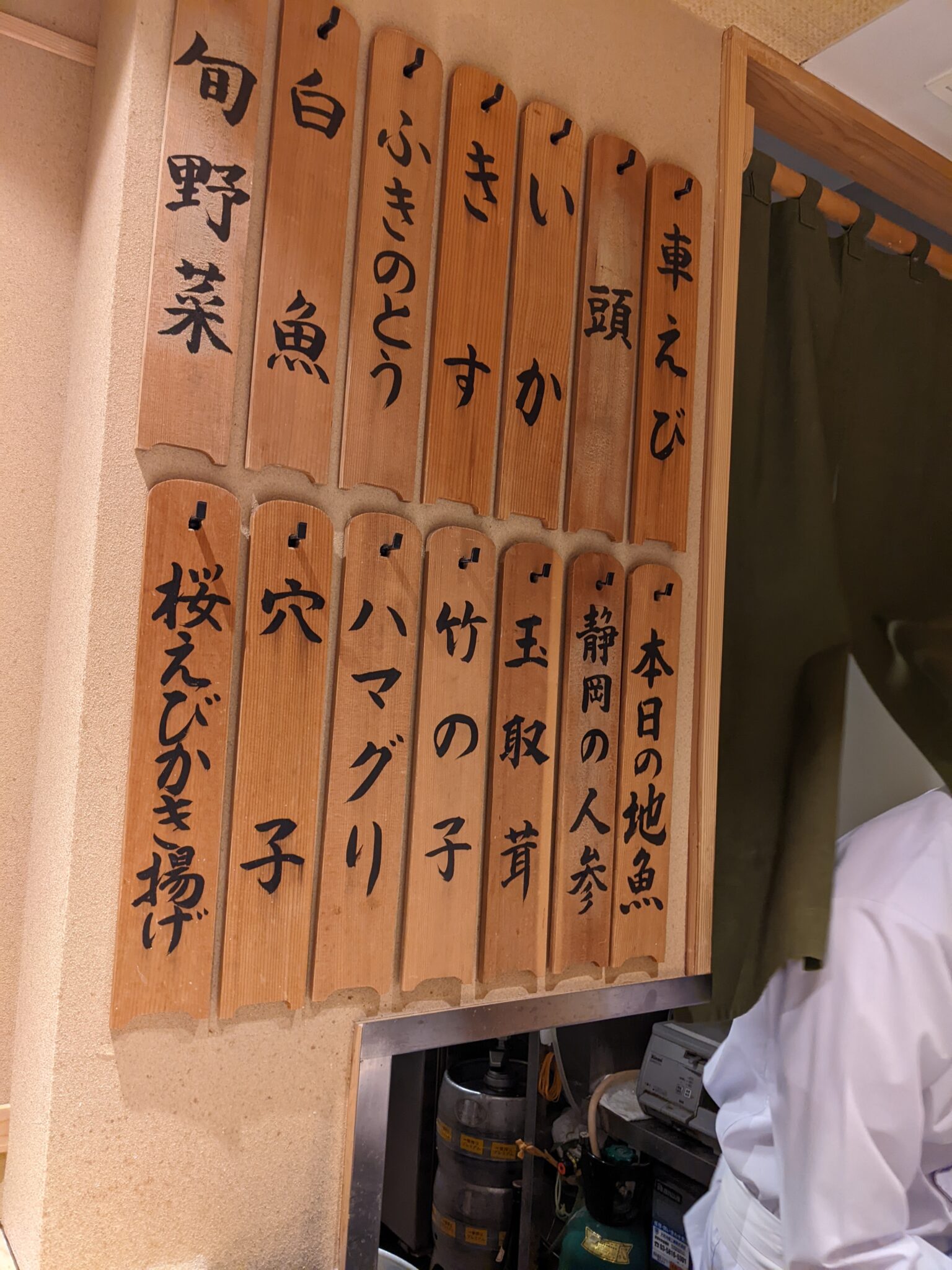

The names of the day’s ingredients are displayed on the wall, each item written on a hanging board, as with some old-style izakaya. Because the wall didn’t have space for everything, the name boards for two additional items were set up on the back counter. When I looked over what we were soon going to be eating I noticed several very seasonal, or shun (旬, pronounced shoon) items, including sakura ebi kakeage, hotaru ika, shin-tamanegi, hamaguri, takenoko—just available as of the previous day—and fukinotō. Lucky us, I said to my wife. We scheduled the meal for just the right day, or at least week.

Our lunch started with a cup of soba-mi (soba seeds) simmered in dashi with nama-nori and a dab of freshly grated wasabi, which was followed by a clear soup made from shijimi (small clams), both of these servings eaten while watching much of the tenpura ingredients being prepared for cooking. And then, for the next two hours, came the tenpura!

First up was two pieces of headless Kurumi ebi, served one at a time. For the first one Suzuki san recommended eating it as is, which we did. A few minutes later the second one was placed on the serving dish in front of me along with advice to use a bit of lemon and salt, which I did. The salt, fairly light and small grained and from Shizuoka was, along with a slice of lemon, on a small plate on the tray on the counter in front of the diners. Next to the salt was a small bowl partially filled with tentsuyu (dipping sauce), with another bowl full of daikon oroshi (grated daikon) off to the side to add to the tentsuyu, the daikon believed to aid digesting the oily tenpura. The shrimp heads were next, again one at a time, the first placed directly into the bowl of tentsuyu, the second on the serving plate with salt the suggested garnish. All were excellent.

The kuruma ebi were followed by two types of ika (squid), first a thick piece of sumi-ika, slightly chewy on the inside, and then two hotaru-ika, a very seasonal item. It may have been the first time I’d ever eaten this as tenpura. More fish came after that, a whole kisu that had had its head cut off and belly cut open, resulting in what resembled a slipper, or maybe one of those Russian (or is it Ukraine?) boots with the extended toe worn for traditional dancing.

Next came a series of vegetables starting with asparagus, first the top half, the spear part, which was meant to be eaten with salt, and then the bottom half which was placed in the tentsuyu. Very delicious, but also very hot due to the moisture inside. Skewers of fukunotō, another very seasonal—shun—item followed, then six or seven shirouo.

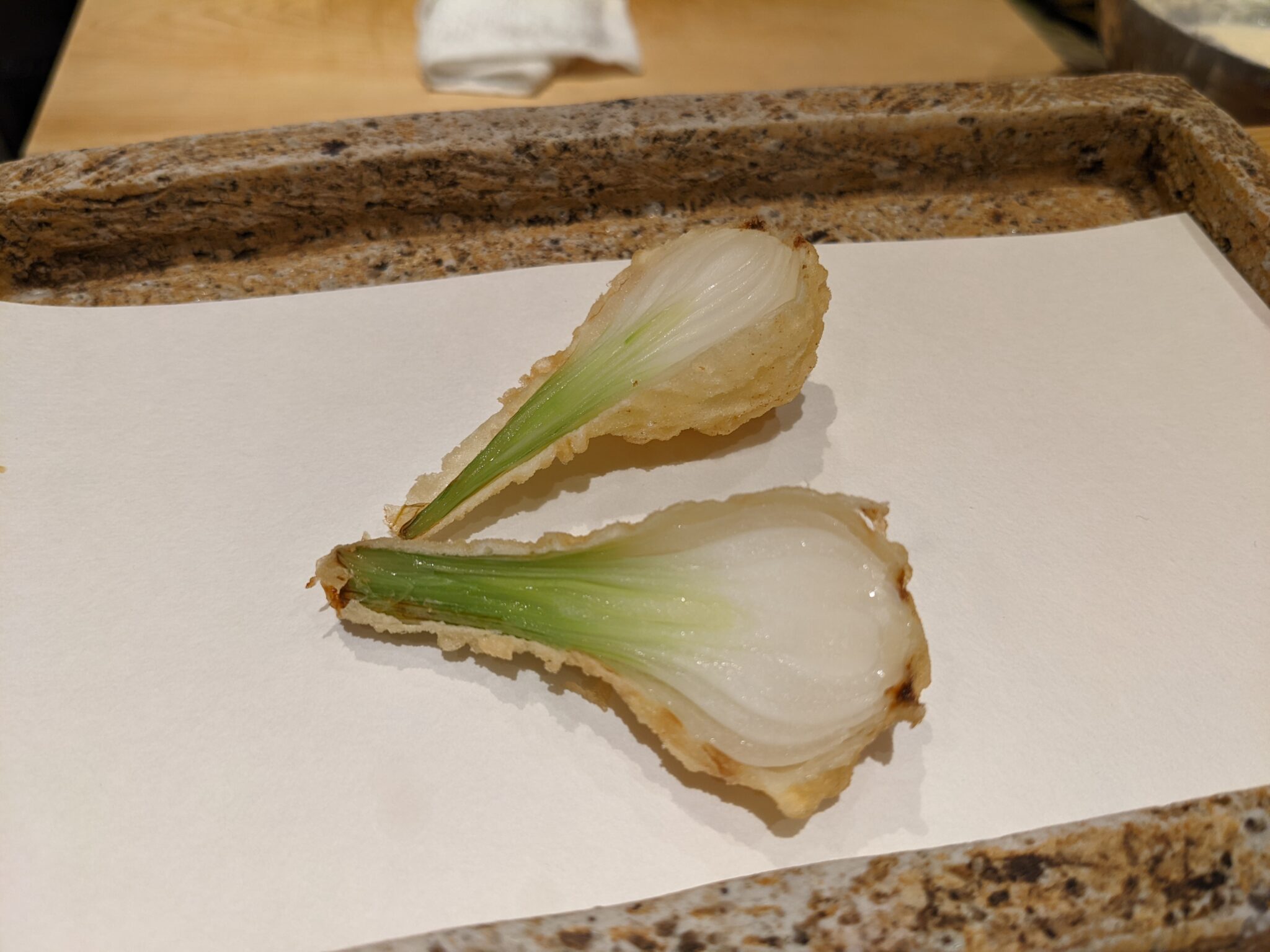

While we were eating all that we were also watching the ingredients being set in front of us on the prep-counter, including some beautiful and small shin-tama-negi (fresh onions) and some mini-tomatoes, or what would be called cherry tomatoes in the US. And sure enough that was what we ate next, the tomatoes, served on skewers, being very sweet, as were the onions which were split in half.

A small mound of soba-gaki came after that, the soba chopped up and mixed with some shoyu with a bit of wasabi on top, and interesting break from the parade of tenpura. I didn’t remember eating the soba-gaki before, but when I asked about it I learned I had indeed had it.

By this point both my wife’s and my own beer were finished, so I asked for some nihonshu, to be selected by okamisan, the owner’s wife. She poured us one tokuri of Isojiman (磯自慢), from Yaizu, Shizuoka (of course), and it paired very nicely with the remainder of the meal, starting with a piece of hirame, served semi-raw in the center. How this is done is a mystery to me, although with practice I could probably learn to do it.

Around this time the chef started preparing what looked like giant shiitake mushrooms, chopping the base of the stems off before quartering them. Before eating them, though, came some Mishima aka ninjin, red carrots grown in fields naturally irrigated by the underground flow of water from Mt. Fuji (Mishima is a city along the coast near the base of the mountain). The carrots were sweet, and not too dangerous to eat as there is not much moisture in them. Takenoko came next. They were from Kyoto and had become available just the previous day, making them an exceptionally seasonal food.

The mushrooms were next, but they were not shiitake but tama-tori-take (玉取茸), from Shizuoka and something I had never been aware of before. But this time we could read the name on the “menu” board hanging on the wall. Hamaguri, another seasonal item served semi-raw and pink in the center, was next, and again cooked to perfection with the center semi-raw. Anago came after that, but not local anago. This was from Tsukushima, the island between Kyushu and the Korean peninsula that is part of Nagasaki Prefecture. The eels were fairly small with a very delicate texture. And delicious! A slice of sweet lemon from—you guessed it—Shizuoka was a sign that the meal was nearing its conclusion. But not before one more tenpura, red inca imo (a type of small reddish potato), one piece cooked minimally, the other a bit longer, giving it a bit of a burnt look to it.

The final course was soba, this time served with fresh sakura ebi kake-age, the mini, pink shrimp from the deep waters off Shizuoka, the only place they are found. I think everyone went with cold soba, made that morning in the basement using one part wheat flour and nine soba flour. Despite the Sonoji being famous for its tenpura, the sign by the front door says soba, not tenpura. The wasabi served on the side was from Utōgi, Shizuoka, (有東木), an area which claims to be where wasabi originated. When I looked it up I found several wasabi farms that are around 400 years old, so the claim to being where wasabi farming originated may have a bit of truth to it. As a closer we were served shin-sen-cha from Shizuoka, and a blackish piece of wagashi that was quite sweet. Guess where it came from.

One thought on “Sonoji Soba & Tenpura 浅ノ字 蕎麦&天ぷら”

What a lovely story! It makes me want to go there and just put myself in the hands of the chef. Then all I have to say is “Omakase, Onigashimasu; Oishī, dusu; and Dōmo arigatōgozaimasu.”